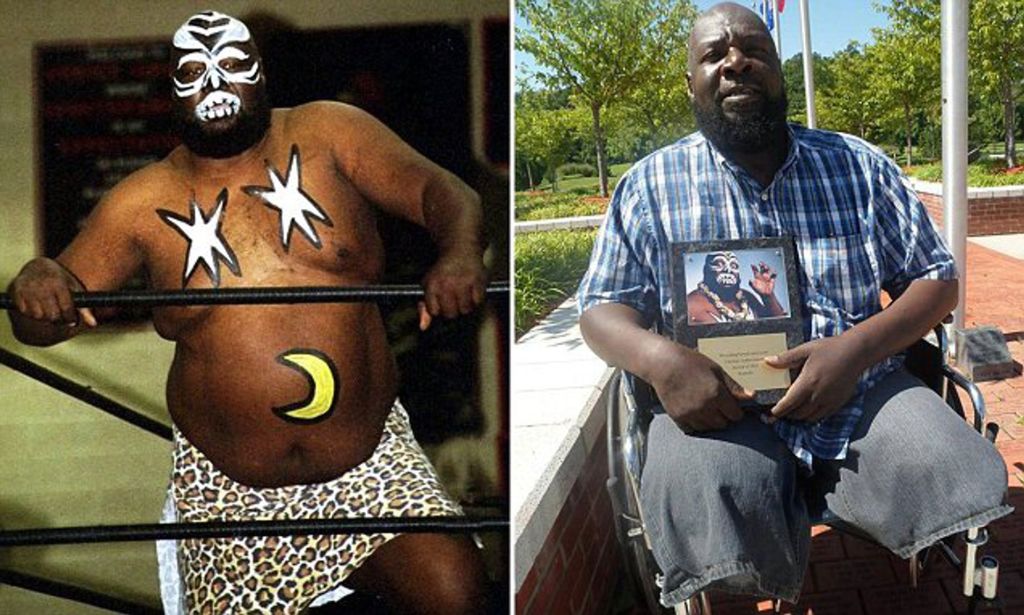

The rhythmic, ominous pounding of tribal drums fills the arena as a masked handler, clad in safari gear, leads a colossal figure to the wrestling ring. The figure is nearly seven feet tall, barefoot, and wears only a loincloth. His face and massive torso are covered in stark war paint, two stars on his chest, a moon on his belly, and he brandishes a spear and shield. This was the terrifying spectacle of Kamala, “The Ugandan Giant,” a character designed to evoke primal fear in audiences throughout the 1980s and 1990s. He was portrayed as a simpleminded, uncontrollable savage, a monster to be vanquished by the era’s greatest heroes.

This carefully constructed nightmare, however, concealed a profoundly different reality. The man behind the paint was James Harris, a quiet, often gentle man born in Senatobia. His life story is a powerful study in contrasts: the on-screen monster versus the off-screen man, the global fame versus the personal hardship, the adoration of fans versus the exploitation by promoters. Harris escaped a life of poverty and limited opportunity by embodying a controversial, racially charged character that brought him worldwide recognition. Yet, this path led to a career marked by financial disputes, physical ruin, and a complicated legacy that the wrestling industry is still attempting to reconcile. This reconciliation is most evident in his posthumous 2025 induction into the WWE Hall of Fame and the signing of a “Legends” contract for his estate, acts that celebrate the performer while raising complex questions about the industry’s historical accountability. These honors, coming years after his death, represent a form of corporate storytelling, an attempt by the industry to reclaim the narrative of one of its most memorable creations. It allows for the celebration of the character’s impact and the performer’s dedication, but it strategically sidesteps the more difficult conversations about the exploitation and financial grievances that Harris voiced until the end of his life.

Forging a Path from Coldwater

Harris was born on May 28, 1950, and grew up in the nearby town of Coldwater. His early life was defined by the harsh realities of the segregated South and a profound personal tragedy. When Harris was just four years old, his father was shot and killed during a dice game, an event that left the family impoverished and set the tone for a life of struggle. To help support his mother and four sisters, the young Harris worked as a sharecropper, picking cotton to make ends meet. The limited opportunities available in that era led him down a difficult path; he left high school in the ninth grade and turned to petty crime, becoming a habitual burglar.

This chapter of his life came to an abrupt end in 1967. Local police, aware of his activities, gave him an ultimatum to leave town or face the consequences. As Harris later recalled, the choice was not really a choice at all. This forced exile set him on a migratory path that would eventually lead him to the wrestling ring. He first relocated to Florida, where he worked manual labor jobs like picking fruit and driving trucks, before moving north to Benton Harbor, Michigan, at age 25. It was there that he had a fateful encounter with the legendary African American wrestler Bobo Brazil, who saw potential in the large young man and agreed to train him.

Harris made his professional debut in 1978, not as a Ugandan monster, but as “Sugar Bear” Harris, a friendly nickname he had earned playing high school football. For four years, he was a journeyman wrestler, honing his craft in the Southern territories under various names like “Ugly Bear” Harris and “Big Jim” Harris. He was a seasoned professional long before he became a household name, winning his first title, the NWA Tri-State Tag Team Championship, with Oki Shikina in 1979. He even gained international experience, wrestling in the United Kingdom as “The Mississippi Mauler,” a brawling character that was a clear precursor to his most famous persona. This early career demonstrates that Harris was not an overnight sensation. He was a dedicated performer who had paid his dues, whose imposing size and presence were simply waiting for the right gimmick to ignite his career. Promoters Jerry Lawler and Jerry Jarrett didn’t invent a wrestler; they invented a character and applied it to an existing, capable, and physically imposing athlete who was ready for the spotlight.

The Birth of a Nightmare: Creating Kamala

In 1982, after sustaining a broken ankle during his European tour, Harris returned home to Mississippi. A chance visit to the Mid-South Coliseum in Memphis to borrow ring attire from a friend led to a meeting with Continental Wrestling Association (CWA) promoter and local wrestling icon, Jerry “The King” Lawler. Lawler, along with his business partner Jerry Jarrett, saw in the 6-foot-7 Harris the perfect vessel for a new, terrifying villain. Together, the three men developed the character of “Kimala” (the spelling was later adjusted to Kamala).

The gimmick was designed to provoke and terrify. The core concept was that of a “wild savage” Ugandan headhunter, with inspirations drawn from a painting by fantasy artist Frank Frazetta, which influenced the distinct face and body paint. Lawler also cited the notorious Ugandan dictator Idi Amin, whose reputation for alleged cannibalism was prominent in the news, as a key influence. The name itself was lifted from a National Geographic article about a city in Uganda. The character’s backstory cast him as a former bodyguard for Amin who had been “discovered” in the jungles of Africa by his first manager, J. J. Dillon.

The creation of Kamala was a masterclass in wrestling myth-making, a business decision that knowingly and successfully weaponized stereotypes for profit. The promoters understood that in the cultural landscape of the early 1980s, a character representing a primitive, cannibalistic African would be a potent and lucrative monster for the local hero, Lawler, to vanquish. The iconic promotional vignettes, which showed a spear-wielding Kamala emerging from a “steamy African jungle,” were actually filmed on Jarrett’s farm in Tennessee, with dry ice providing the fog effect. To establish the character’s monstrous nature, Jarrett instructed Harris to use a simplistic, brawling style focused on wild chops and biting. The overhand chops, which became a signature move, were reportedly suggested by Lawler as a replacement for Harris’s unconvincing punches.

Harris’s commitment to the role was absolute, a key factor in its success. To preserve kayfabe, he wore robes in public, refused to speak English, and never broke character by laughing or smiling. He was the silent, terrifying giant 24/7. The formula worked instantly. Kamala’s debut match against Lawler in May 1982 sold out the Mid-South Coliseum. Just one month later, he defeated Lawler to win the AWA Southern Heavyweight Championship, cementing his status as an immediate main-event attraction. The character’s success was a direct result of a product perfectly tailored to generate heat and draw money in its time and place.

Unleashing the Giant on the Territories

Following his explosive debut in Memphis, Kamala became one of the most in-demand attractions in the territorial wrestling system of the 1980s. His career pattern during this era reveals his primary function in the wrestling ecosystem as a traveling “special attraction”. His role was to enter a new territory for a short, intense period, establish himself as an unstoppable monster, create a massive threat for the local hero to conquer, draw huge money at the box office, and then move on to the next promotion to repeat the cycle.

In late 1982, he joined Bill Watts’ influential Mid-South Wrestling promotion, a hotbed of talent based in Louisiana and Oklahoma. There, he was managed by the villainous Skandor Akbar as part of his “Devastation, Inc.” stable, with his ever-present handler, “Friday”. In Mid-South, he engaged in a memorable “battle of the monsters” series against another powerful African American superstar, The Junkyard Dog, and began his legendary feud with André the Giant, which culminated in a match that drew over 21,000 fans to the Louisiana Superdome.

In 1983, he moved on to the Dallas-based World Class Championship Wrestling (WCCW), where he became a top villain against the territory’s beloved heroes, the Von Erich family. He had notable feuds with brothers David, Kevin, and Kerry and holds the somber distinction of being David’s final opponent before his sudden death in 1984. His tour of the territories also included a stop in the American Wrestling Association (AWA), where he feuded with Sgt. Slaughter in a “Ugandan Death Match”. This model maximized his value as a traveling draw but also reinforced the narrative that he was a monster to be slain, not a champion to be built around. It was a pattern that would define his later, more famous runs in the World Wrestling Federation.

Major Championships and Honors

While he famously won no championships during his WWF/WWE stints, his title history in the territories demonstrates his success and credibility as a top-level performer before his national runs.

NWA Tri-State United State Tag Team Championship. He won his first title in 1979 with Oki Shikina, billed as “Sugar Bear” Harris.

Southeastern Championship Wrestling NWA Southeastern Heavyweight Championship. He held the title in 1980 billed as “Bad News” Harris.

Continental Wrestling Association AWA Southern Heavyweight Championship. In 1982, Harris defeated Jerry “The King Lawler” for the title.

United States Wrestling Association Unified World Heavyweight Championship. In 1991-92, he held the title for four separate times for a combined 125 days.

2012 Texas Wrestling Hall of Fame

2025 Legacy wing of the WWE Hall of Fame, inducted posthumously.

Clashes of the Titans: The WWF Years

Kamala had multiple stints with the World Wrestling Federation (now WWE), where he was consistently presented as a main-event-level monster heel pitted against the promotion’s biggest stars. These feuds became the most visible and defining moments of his career.

The Battle of the Giants (vs. André the Giant)

The feud between Kamala and André the Giant, which began in Mid-South, was brought to the WWF in 1984, reportedly at the insistence of André himself. It was a promoter’s dream: a legitimate “battle of the giants” that captivated audiences across the country. Their program included a famous steel cage match in October 1984, which Kamala lost after André sat on his chest twice, a finish that emphasized André’s overwhelming size. While in Mid-South, Kamala had famously bodyslammed and bloodied André, a rare feat that instantly established him as a credible threat to the “Eighth Wonder of the World”.

More revealing than their in-ring battles was a legendary backstage confrontation that shattered the “simpleminded savage” kayfabe and showed the reality of the man playing the part. After he made a mistake in the ring, an angry André verbally berated him. The next day, Harris confronted the giant in the locker room. With a .357 handgun concealed in his pocket for protection, a measure he took for years, Harris warned André never to disrespect him like that again. A surprised André immediately apologized, calling Harris “Boss” from that day forward, a term he used as a sign of respect. It was a calculated act of courage that demonstrated a keen understanding of power dynamics, proving the man behind the paint was anything but simple.

Challenging Hulkamania (vs. Hulk Hogan)

From late 1986 to early 1987, Kamala was positioned as the primary challenger for Hulk Hogan’s WWF World Heavyweight Championship, marking the pinnacle of his career. This feud was a massive box-office success, selling out major arenas like New York’s Madison Square Garden and Toronto’s Maple Leaf Gardens multiple times. The matches followed the classic Hogan formula: Kamala, flanked by his manager The Wizard and handler Kim Chee, would dominate the champion with his savage offense, only for Hogan to make his iconic “Hulk up” comeback for the victory. Though the outcome was never in doubt, the spectacle of the seemingly unstoppable monster challenging the ultimate hero drew enormous crowds who viewed Kamala as a legitimate threat.

This period also highlighted Harris’s sharp business acumen. He famously quit the WWF in 1987 rather than agree to lose to Hogan in a high-profile match on the nationally televised Saturday Night’s Main Event. Harris understood that a definitive, clean loss on network television would permanently damage his monster aura, killing his value as a top attraction in other territories. He wisely chose to preserve the power of his gimmick over a single payday, demonstrating a savvy understanding of his own brand that contradicted his on-screen persona.

Facing The Phenom (vs. The Undertaker)

When Kamala returned to the WWF in 1992, he was immediately thrust into a feud with another of the era’s great supernatural characters, The Undertaker. The rivalry was built on psychological warfare, with The Undertaker and his manager, Paul Bearer, exploiting Kamala’s character’s purported terror of death and coffins, a fear that Harris admitted was genuine, as he suffered from claustrophobia.

The feud culminated in the first-ever televised “Coffin Match” (later known as the Casket Match) at Survivor Series in November 1992. In a memorable finish, The Undertaker struck Kamala with his mystical urn and rolled him into the casket for the victory, before symbolically nailing the lid shut. While the match was a landmark moment in WWE history, it became a source of great bitterness for Harris. In his autobiography and subsequent interviews, he claimed a massive pay disparity for the event. He stated that he saw a pay sheet indicating he was paid only $13,000 for the match, while his opponent, The Undertaker, received $500,000. This alleged incident became a cornerstone of Harris’s belief that he was treated unfairly and faced bias when it came to compensation from the company.

The Man Behind the Paint: “Kamala Speaks”

For over 30 years, Harris’s character never spoke a word on camera, his story always told for him by his managers. In 2015, he broke that silence with the release of his autobiography, Kamala Speaks, co-written with Kenny Casanova. The book was a definitive act of breaking kayfabe, not just for the character, but for the man. It was Harris’s chance to seize control of his own narrative, to separate the man from the monster, and to hold the industry accountable for its treatment of him. The book’s very title is a powerful refutation of the silent, simpleminded persona he portrayed for decades.

The autobiography delves into the difficult themes that defined his life and career. A central focus is his experience with what he perceived as systemic racism and pay disparity within the wrestling industry. He details numerous instances where he felt his compensation and opportunities were limited because of his race, with the alleged pay gap for his Survivor Series match against The Undertaker serving as his prime example. However, the book is framed not as a bitter complaint, but as an inspirational story of survival. Harris recounts overcoming immense personal obstacles, including the murder of his father and, later, his sister and niece, his long and painful battle with diabetes, and his journey from the poverty of a sharecropper’s family to global stardom.

Harris also gives his own perspective on the controversial gimmick. He makes it clear that he viewed the character as a performance. He understood the role he was asked to play and dedicated himself to it to provide for his family. His issue was never with the character itself, but with the lack of respect and fair compensation he felt he received while portraying it.

Kamala Speaks is a reclamation project, a powerful statement that the “Ugandan Giant” was, in fact, a thinking, feeling, and observant man who remembered every slight and every kindness.

The Long Sunset: Life After Wrestling

Harris’s in-ring career wound down in the 2000s, with his final independent circuit match taking place in 2010. His life after wrestling was marked by severe health issues and financial hardship. He was first diagnosed with diabetes in 1992 but struggled to manage the condition, which eventually led to devastating complications. In November 2011, his left leg was amputated below the knee; less than five months later, in April 2012, his right leg was also amputated, leaving him permanently confined to a wheelchair.

These health problems created immense financial strain, leading to the establishment of charity funds to help with his needs. In 2016, Harris joined a class-action lawsuit against WWE that alleged the company had concealed the long-term risks of traumatic brain injuries suffered by its performers. The lawsuit, which included many other former wrestlers, was ultimately dismissed by a federal judge in 2018.

Throughout these struggles, Harris was supported by his family. He was married twice, first to Clara Freeman, a marriage that ended in divorce, and later to Emmer Jean Bradley, who remained with him until his death. He was the father of six children, five daughters and one son. His health continued to decline, and in 2017 he underwent life-saving emergency surgery to clear fluid from around his heart and lungs. On August 5, 2020, he was hospitalized after testing positive for COVID-19. Four days later, on August 9, 2020, Harris died in a hospital in Oxford from cardiac arrest brought on by complications from COVID-19 and diabetes. He was 70 years old.

Beyond the ring, Harris revealed other facets of his personality. In a surprising turn, he pursued a music career and released a synth-pop album titled The Best of Kamala, which showcased a side of him fans had never seen. He also appeared in the 1993 Hulk Hogan film Mr. Nanny. In a quirky piece of wrestling history, a rare variant of his 1990s Hasbro action figure, one with a moon painted on the belly instead of the common star, is now considered one of the most valuable and sought-after wrestling collectibles in existence.

Reconciling the Legacy

The legacy of James “Kamala” Harris is a powerful, cautionary, and deeply conflicted one, split between the unforgettable character he portrayed and the resilient man he was. The character, Kamala “The Ugandan Giant,” remains one of the most memorable and effective monster heels in professional wrestling history. He was a terrifying spectacle who drew massive money and created indelible moments against the sport’s most iconic figures, from Jerry Lawler to Hulk Hogan to The Undertaker. He was a master of his role, a consummate performer who embodied a larger-than-life persona with terrifying believability.

Harris leaves behind a different but equally powerful legacy. He was a kind and respected individual who overcame a life of unimaginable hardship, from poverty and family tragedy to the brutal politics of the wrestling business. Yet, he was also a victim of an exploitative system that profited immensely while, by his own account, leaving him physically and financially broken.

It is impossible to separate the performer from the performance, and in the modern era, the Kamala gimmick is rightfully viewed as a product of its time.

While Harris himself was an African American making a living in a world with few opportunities, the character he played is an indictment of the industry that created it. His story is a testament to his incredible talent and his profound strength as a human being. He was a pioneer who, as his autobiography asserts, helped break down barriers for future African American wrestlers, but he did so by playing a role that reinforced the very stereotypes that built those barriers.

The posthumous honors from WWE are a belated acknowledgment of the character’s undeniable impact, but the true, enduring legacy of James Harris lies in the complex, triumphant, and often tragic story of the man who brought the monster to life.

Leave a reply to sopantooth Cancel reply